Scientific Guide to Snacking

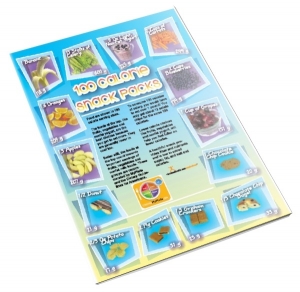

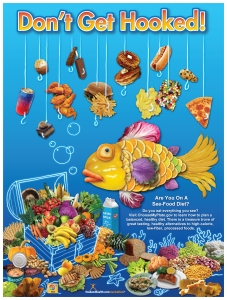

Our Nutrition Month celebration continues with a scientific guide to snacking. The guide was crafted by James J. Kenney, PhD, FACN. Though originally written solely for our member library, part of this article is now available here -- just for you. Still, you should go ahead and sign up for the member library -- it's chock-full of the latest science, articles, research, games, and more. So before you dive into our snacking guide, go ahead and register for our library too.Anyway, on to the snacking guide!Did you know that snacking when you're not hungry may promote weight gain? Researchers in one recent study fed subjects a 400-calorie snack at various times after eating a 1,300-calorie lunch. They found that when subjects consumed a snack when they were not hungry, there would not be a difference in the time they requested dinner or in the amount of food they ate at dinner (1). The results of this study suggest that snacking when not hungry may promote increased calorie intake and weight gain over time.Eating breakfast may impact snacking behavior in overweight people. Many obese people skip breakfast. However, a study that randomly assigned overweight people to various weight-loss programs showed that those who consumed breakfast lost significantly more weight over a 12-week program (2). This may be because those who skip breakfast tend to select more calorie-dense foods later in the day than those who regularly eat breakfast (3).Eating smaller, more frequent meals does appear to shrink the size of the stomach. A study that examined the stomach capacity of people on a very-low-calorie diet for 4 weeks showed that stomach size was reduced by 27 to 36% compared to control subjects who maintained their usual eating habits (4). This study suggests that people who regularly eat smaller, more frequent meals will begin to feel more satisfied with less food over time. In theory, this might be why people who eat smaller, but more frequent meals tend to be thinner on average.Any metabolic advantage from snacking or eating more frequent meals obviously disappears if the total calorie intake increases. A study of eight young men with a normal weight examined the impact of consuming no snack versus a high-protein or high-carbohydrate snack. These snacks were given when subjects were not hungry. The subjects were blinded to time and were given the snacks between lunch and dinner. The high-protein snack did delay (by 38 minutes) when the evening meal was requested, but it did not reduce the total calorie intake compared to when no snack was offered. Calorie intake was slightly higher with the high-protein snack compared to no snack. It was even higher with the high-carbohydrate snack than with no snack or the high-protein snack. The authors conclude, “a snack consumed in a non-hungry state has poor satiating efficiency irrespective of its composition, which is evidence that snacking plays a role in obesity” (5).The Bottom LineClearly snacking when you are not hungry is a bad idea if you want to lose weight. If you eat because you are bored, anxious, angry or simply because it looks so good, you will likely end up heavier in the long run. More research is needed to further clarify the metabolic impact of snacking or increasing meal frequency on weight control and overall health. However, based on the available evidence, eating more natural, high-fiber foods like fruits, vegetables and whole grains should be encouraged for those who wish to lose weight without hunger. Meals that contain these foods have been proven to reduce calorie intake. Over time this might lead to an increase in meal frequency, which is OK. It seems likely that eating low-calorie foods will naturally lead to a meal pattern that improves glucose tolerance and lowers plasma concentrations of insulin, fasting and postprandial triglycerides and LDL. Such metabolic improvements should reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease.When rich, highly palatable foods, such as cookies, chips and muffins, are readily available, food consumption may be triggered by the pleasurable taste of those foods and not true hunger (6). It appears that humans do not have the ability to prevent overeating when they have constant access to highly palatable foods high in fats, refined grains and sugars (7). Eating more natural foods and being more active is the key to weight control.By James J. Kenney, PhD, FACNReferences:1. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;70:854-662. Am J Clin Nutr 1992;55:645-513. J Am Coll Nutr 1986;5:551-634. J Am Coll Nutr 1996;63:170-35. J Am Coll Nutr 2002;76:518-286. Appetite 1998;30:211-227. Lancet 2000;355:8For the full article, including the basic guide to snacking, join our member library. If you're already a member, click here to get the rest of the article...Or download this free snacking handout today!Happy Nutrition Month!

Our Nutrition Month celebration continues with a scientific guide to snacking. The guide was crafted by James J. Kenney, PhD, FACN. Though originally written solely for our member library, part of this article is now available here -- just for you. Still, you should go ahead and sign up for the member library -- it's chock-full of the latest science, articles, research, games, and more. So before you dive into our snacking guide, go ahead and register for our library too.Anyway, on to the snacking guide!Did you know that snacking when you're not hungry may promote weight gain? Researchers in one recent study fed subjects a 400-calorie snack at various times after eating a 1,300-calorie lunch. They found that when subjects consumed a snack when they were not hungry, there would not be a difference in the time they requested dinner or in the amount of food they ate at dinner (1). The results of this study suggest that snacking when not hungry may promote increased calorie intake and weight gain over time.Eating breakfast may impact snacking behavior in overweight people. Many obese people skip breakfast. However, a study that randomly assigned overweight people to various weight-loss programs showed that those who consumed breakfast lost significantly more weight over a 12-week program (2). This may be because those who skip breakfast tend to select more calorie-dense foods later in the day than those who regularly eat breakfast (3).Eating smaller, more frequent meals does appear to shrink the size of the stomach. A study that examined the stomach capacity of people on a very-low-calorie diet for 4 weeks showed that stomach size was reduced by 27 to 36% compared to control subjects who maintained their usual eating habits (4). This study suggests that people who regularly eat smaller, more frequent meals will begin to feel more satisfied with less food over time. In theory, this might be why people who eat smaller, but more frequent meals tend to be thinner on average.Any metabolic advantage from snacking or eating more frequent meals obviously disappears if the total calorie intake increases. A study of eight young men with a normal weight examined the impact of consuming no snack versus a high-protein or high-carbohydrate snack. These snacks were given when subjects were not hungry. The subjects were blinded to time and were given the snacks between lunch and dinner. The high-protein snack did delay (by 38 minutes) when the evening meal was requested, but it did not reduce the total calorie intake compared to when no snack was offered. Calorie intake was slightly higher with the high-protein snack compared to no snack. It was even higher with the high-carbohydrate snack than with no snack or the high-protein snack. The authors conclude, “a snack consumed in a non-hungry state has poor satiating efficiency irrespective of its composition, which is evidence that snacking plays a role in obesity” (5).The Bottom LineClearly snacking when you are not hungry is a bad idea if you want to lose weight. If you eat because you are bored, anxious, angry or simply because it looks so good, you will likely end up heavier in the long run. More research is needed to further clarify the metabolic impact of snacking or increasing meal frequency on weight control and overall health. However, based on the available evidence, eating more natural, high-fiber foods like fruits, vegetables and whole grains should be encouraged for those who wish to lose weight without hunger. Meals that contain these foods have been proven to reduce calorie intake. Over time this might lead to an increase in meal frequency, which is OK. It seems likely that eating low-calorie foods will naturally lead to a meal pattern that improves glucose tolerance and lowers plasma concentrations of insulin, fasting and postprandial triglycerides and LDL. Such metabolic improvements should reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease.When rich, highly palatable foods, such as cookies, chips and muffins, are readily available, food consumption may be triggered by the pleasurable taste of those foods and not true hunger (6). It appears that humans do not have the ability to prevent overeating when they have constant access to highly palatable foods high in fats, refined grains and sugars (7). Eating more natural foods and being more active is the key to weight control.By James J. Kenney, PhD, FACNReferences:1. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;70:854-662. Am J Clin Nutr 1992;55:645-513. J Am Coll Nutr 1986;5:551-634. J Am Coll Nutr 1996;63:170-35. J Am Coll Nutr 2002;76:518-286. Appetite 1998;30:211-227. Lancet 2000;355:8For the full article, including the basic guide to snacking, join our member library. If you're already a member, click here to get the rest of the article...Or download this free snacking handout today!Happy Nutrition Month!