Eat the Rainbow?

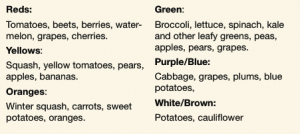

While the value of eating a variety of fruits and vegetables (F&V) is hard to overstate, implementation of the recent “eat- the-rainbow” movement can be oversimplified.1 Basing your F&V diet on the selection of different colors can provide nutriment variety, but not if color is the sole criterion. One reason for this is that the same color in different F&Vs is often due to different nutritive substances. Consequently, eating two different fruits or vegetables of the same color can provide different sets of health benefits despite the similarity of hue. A good example of this is the nutriment differences between the red colors of tomatoes and cranberries. While the red tinge of tomatoes is produced by lycopene that in cranberries results from a group of substances called anthocyanins. There is appreciable evidence that suggests that lycopene affords us protection against several cancers, particularly of the prostate.2 Among the anthocyanins there may also be cancer chemoprotecants, but other molecules in this mix are best known for their proven defense against bladder infections.3 However, these substances rarely occur together naturally; tomatoes contain only traces of anthocyanins while there is no lycopene in cranberries. This means that restricting your consumption of red fruits and vegetables to tomatoes may reduce your risk of prostate cancer, but it won’t help if you’re prone to bladder infections. Likewise, cranberry red will promote urinary health, but probably won’t decrease your risk of a prostate tumor.A second complication of the F&V rainbow results from the recent proliferation of multi-colored produce. Recognizing a marketing opportunity in the rainbow initiative, agricultural producers have given us novel- ties like yellow beets, purple carrots, and even blue potatoes. However, color differences in the same fruit or vegetable aren’t necessarily produced by different substances. Often the color variety is simply a difference in the amounts of the same substance. For example, the red, yellow, and orange varieties of tomatoes are not attributable to different pigments, but to different amounts of the same pigment: lycopene. The yellow and orange varieties simply have lower concentrations of this substance. Therefore, eating a yellow tomato doesn’t give you a different set of health benefits, just less of those you’d get from the red variety. On the other hand, consumption of a different orange fruit or vegetable like sweet potatoes, cantaloupe, or carrots, may provide protection against macular degeneration. Their color is a result of beta-carotene, a pigment that is converted to vitamin A, a requirement for healthy eyes.The evidence that supports the positive health benefits of “eating the rainbow” is already substantial with more published daily. However, “eating the rainbow” should be coupled with consuming the same col- ors from different F&V sources. Choosing a variety of colors is good; choosing a variety of F&V colors and color sources is even better.By Dale E. Vitale, PhD, Chemistry-Physics Dept, Kean UniversityReferences: 1. Garden-Robinson J. 2009,What Color is Your Food?http://www.ag.ndsu.edu/ pubs/yf/foods/fn595w.htm2. Ford NA, Elsen AC, Zuniga K, Lindshield BL, Erdman JW. Nutr Cancer. 2011 Jan 3:1. [Epub ahead of print]3. Côté J, Caillet S, Doyon G, Sylvain JF, Lacroix M. 2010. Bioactive compounds in cran. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 50(7):666-79.

While the value of eating a variety of fruits and vegetables (F&V) is hard to overstate, implementation of the recent “eat- the-rainbow” movement can be oversimplified.1 Basing your F&V diet on the selection of different colors can provide nutriment variety, but not if color is the sole criterion. One reason for this is that the same color in different F&Vs is often due to different nutritive substances. Consequently, eating two different fruits or vegetables of the same color can provide different sets of health benefits despite the similarity of hue. A good example of this is the nutriment differences between the red colors of tomatoes and cranberries. While the red tinge of tomatoes is produced by lycopene that in cranberries results from a group of substances called anthocyanins. There is appreciable evidence that suggests that lycopene affords us protection against several cancers, particularly of the prostate.2 Among the anthocyanins there may also be cancer chemoprotecants, but other molecules in this mix are best known for their proven defense against bladder infections.3 However, these substances rarely occur together naturally; tomatoes contain only traces of anthocyanins while there is no lycopene in cranberries. This means that restricting your consumption of red fruits and vegetables to tomatoes may reduce your risk of prostate cancer, but it won’t help if you’re prone to bladder infections. Likewise, cranberry red will promote urinary health, but probably won’t decrease your risk of a prostate tumor.A second complication of the F&V rainbow results from the recent proliferation of multi-colored produce. Recognizing a marketing opportunity in the rainbow initiative, agricultural producers have given us novel- ties like yellow beets, purple carrots, and even blue potatoes. However, color differences in the same fruit or vegetable aren’t necessarily produced by different substances. Often the color variety is simply a difference in the amounts of the same substance. For example, the red, yellow, and orange varieties of tomatoes are not attributable to different pigments, but to different amounts of the same pigment: lycopene. The yellow and orange varieties simply have lower concentrations of this substance. Therefore, eating a yellow tomato doesn’t give you a different set of health benefits, just less of those you’d get from the red variety. On the other hand, consumption of a different orange fruit or vegetable like sweet potatoes, cantaloupe, or carrots, may provide protection against macular degeneration. Their color is a result of beta-carotene, a pigment that is converted to vitamin A, a requirement for healthy eyes.The evidence that supports the positive health benefits of “eating the rainbow” is already substantial with more published daily. However, “eating the rainbow” should be coupled with consuming the same col- ors from different F&V sources. Choosing a variety of colors is good; choosing a variety of F&V colors and color sources is even better.By Dale E. Vitale, PhD, Chemistry-Physics Dept, Kean UniversityReferences: 1. Garden-Robinson J. 2009,What Color is Your Food?http://www.ag.ndsu.edu/ pubs/yf/foods/fn595w.htm2. Ford NA, Elsen AC, Zuniga K, Lindshield BL, Erdman JW. Nutr Cancer. 2011 Jan 3:1. [Epub ahead of print]3. Côté J, Caillet S, Doyon G, Sylvain JF, Lacroix M. 2010. Bioactive compounds in cran. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 50(7):666-79.